Is our pursuit of economic growth blinding us to ecological disaster? Discover how conventional economics could be leading us astray with David Suzuki.

“The Great Agricultural Takeover” is a compelling short video that examines the profound transformation in agriculture from traditional farming to industrial practices post-World War II. This six-minute presentation highlights how technologies developed for warfare were repurposed to dramatically alter agricultural methods. It narrates the historical decisions led by groups like the Committee for Economic Development, which pushed for a reduction in the rural populace to foster a transition towards an industrial workforce, fundamentally changing the farming landscape.

The video explores the significant consequences of substituting mechanical and chemical technologies for human labor. It portrays how farms evolved into factory-like entities, emphasizing efficiency and automation over ecological and social sustainability. This shift not only redefined the relationship between humans and the land but also escalated a silent conflict against the natural world, where the drive for industrial efficiency often overshadows the well-being of ecosystems and rural communities.

Through compelling visuals and insightful narration, “The Great Agricultural Takeover” challenges viewers to reflect on the true cost of industrial agriculture. It calls for a critical reevaluation of current practices and advocates for a return to more sustainable and conscientious farming methods. This narrative urges viewers to consider alternative agricultural models that prioritize land stewardship, sustainability, and community well-being, ensuring a viable future for global food systems.

The industrial economy from agriculture to war is by far the most violent the world has ever known. It is a fact that at the end of world war two industry geared up to adapt the mechanical and chemical technologies of war to agriculture.

At the same time certain corporate and academic leaders, known collectively as the Committee for Economic Development, decided that there were too many farmers. The relatively self-sufficient producers on small farms needed to become members of the industrial labour force and consumers of industrial commodities.

The first problem of a drastic reduction of the land using population is to keep the land producing in the absence of the people. The Committee for Economic Development had a ready solution; the absent people would be replaced by the mechanical and chemical technologies developed for military use and subsisting upon a seemingly limitless bounty of natural resources.

All of the land using population have left their family farms and moved into the cities to be industrially or professionally employed or unemployed and to be entirely dependent upon the ways and the products of industrialism.

Agriculture would become an industry, farms would become factories, like other factories ever more automated and remotely controlled. Industrial land use became a front in a war against the living world.

There is, in fact, no significant difference between the mass destruction of warfare and the massive destruction of industrial land abuse. In order to mine a seam of coal we destroy a mountain, its topsoil and its forest, with no regard for the ecosystem or for the people downhill, downstream and later in time.

But there was another problem that the population engineers did not recognise then and have not recognised yet; agricultural production without land maintenance leads to exhaustion. Land that is in use, if the use is to continue, must be used with care, and care is not and can never be an industrial product or an industrial result.

A proper economy would not exploit, syphon away and finally destroy the life of the land and the people. A proper economy instead would recognise value, cultivate and conserve in any given place, everything that is good in it and worth conserving.

If farming is no more than an industry to be unendingly transformed by technologies then farmers can be replaced by engineers and engineers finally by robots in the progress toward our evident goal of human uselessness. If, on the contrary, because of the uniqueness and fragility of each one of the world’s myriad small places the land economies must involve a creaturely affection and care, then we must see and respect the inescapable dependence even of our present economy, as of our lives, upon nature and the natural world

Good work in the use of the land is work that goes beyond production to maintenance. Production must not reduce productivity. Good work is also informed in locally adapted ways that must be passed down, taught, and learned, generation after generation.

Every mine will eventually be exhausted but a farm, a ranch, or a forest where the laws of nature are observed and obeyed in use, if given sufficient skill as we know they can be, will remain fertile and productive as long as nature lasts.

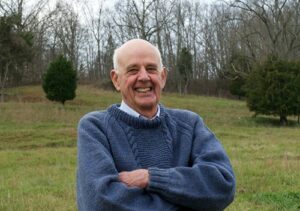

Critics and scholars have acknowledged Wendell Berry as a master of many literary genres, but whether he is writing poetry, fiction, or essays, his message is essentially the same: humans must learn to live in harmony with the natural rhythms of the earth or perish. His book The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture (1977), which analyzes the many failures of modern, mechanized life, is one of the key texts of the environmental movement. Berry has criticized environmentalists as well as those involved with big businesses and land development. In his opinion, many environmentalists place too much emphasis on wild lands without acknowledging the importance of agriculture to our society. Berry strongly believes that small-scale farming is essential to healthy local economies, and that strong local economies are essential to the survival of the species and the wellbeing of the planet.

Critics and scholars have acknowledged Wendell Berry as a master of many literary genres, but whether he is writing poetry, fiction, or essays, his message is essentially the same: humans must learn to live in harmony with the natural rhythms of the earth or perish. His book The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture (1977), which analyzes the many failures of modern, mechanized life, is one of the key texts of the environmental movement. Berry has criticized environmentalists as well as those involved with big businesses and land development. In his opinion, many environmentalists place too much emphasis on wild lands without acknowledging the importance of agriculture to our society. Berry strongly believes that small-scale farming is essential to healthy local economies, and that strong local economies are essential to the survival of the species and the wellbeing of the planet.

“Robotics leads to human uselessness. It means a lot. We are building a road to self destruction.”

For more on the speaker, please visit his website.

Music:

“The Great Agricultural Takeover” is a compelling short video that examines the profound transformation in agriculture from traditional farming to industrial practices post-World War II. This six-minute presentation highlights how technologies developed for warfare were repurposed to dramatically alter agricultural methods. It narrates the historical decisions led by groups like the Committee for Economic Development, which pushed for a reduction in the rural populace to foster a transition towards an industrial workforce, fundamentally changing the farming landscape.

The video explores the significant consequences of substituting mechanical and chemical technologies for human labor. It portrays how farms evolved into factory-like entities, emphasizing efficiency and automation over ecological and social sustainability. This shift not only redefined the relationship between humans and the land but also escalated a silent conflict against the natural world, where the drive for industrial efficiency often overshadows the well-being of ecosystems and rural communities.

Through compelling visuals and insightful narration, “The Great Agricultural Takeover” challenges viewers to reflect on the true cost of industrial agriculture. It calls for a critical reevaluation of current practices and advocates for a return to more sustainable and conscientious farming methods. This narrative urges viewers to consider alternative agricultural models that prioritize land stewardship, sustainability, and community well-being, ensuring a viable future for global food systems.

The industrial economy from agriculture to war is by far the most violent the world has ever known. It is a fact that at the end of world war two industry geared up to adapt the mechanical and chemical technologies of war to agriculture.

At the same time certain corporate and academic leaders, known collectively as the Committee for Economic Development, decided that there were too many farmers. The relatively self-sufficient producers on small farms needed to become members of the industrial labour force and consumers of industrial commodities.

The first problem of a drastic reduction of the land using population is to keep the land producing in the absence of the people. The Committee for Economic Development had a ready solution; the absent people would be replaced by the mechanical and chemical technologies developed for military use and subsisting upon a seemingly limitless bounty of natural resources.

All of the land using population have left their family farms and moved into the cities to be industrially or professionally employed or unemployed and to be entirely dependent upon the ways and the products of industrialism.

Agriculture would become an industry, farms would become factories, like other factories ever more automated and remotely controlled. Industrial land use became a front in a war against the living world.

There is, in fact, no significant difference between the mass destruction of warfare and the massive destruction of industrial land abuse. In order to mine a seam of coal we destroy a mountain, its topsoil and its forest, with no regard for the ecosystem or for the people downhill, downstream and later in time.

But there was another problem that the population engineers did not recognise then and have not recognised yet; agricultural production without land maintenance leads to exhaustion. Land that is in use, if the use is to continue, must be used with care, and care is not and can never be an industrial product or an industrial result.

A proper economy would not exploit, syphon away and finally destroy the life of the land and the people. A proper economy instead would recognise value, cultivate and conserve in any given place, everything that is good in it and worth conserving.

If farming is no more than an industry to be unendingly transformed by technologies then farmers can be replaced by engineers and engineers finally by robots in the progress toward our evident goal of human uselessness. If, on the contrary, because of the uniqueness and fragility of each one of the world’s myriad small places the land economies must involve a creaturely affection and care, then we must see and respect the inescapable dependence even of our present economy, as of our lives, upon nature and the natural world

Good work in the use of the land is work that goes beyond production to maintenance. Production must not reduce productivity. Good work is also informed in locally adapted ways that must be passed down, taught, and learned, generation after generation.

Every mine will eventually be exhausted but a farm, a ranch, or a forest where the laws of nature are observed and obeyed in use, if given sufficient skill as we know they can be, will remain fertile and productive as long as nature lasts.

“Robotics leads to human uselessness. It means a lot. We are building a road to self destruction.”

For more on the speaker, please visit his website.

Music:

Find out how video storytelling can help your audience resonate with your sustainable idea, research, campaign or product.

We never send solicitations or junk mail and we never give your address to anyone else.