What is at the root of the mass shootings and culture of gun violence that plagues the United States?

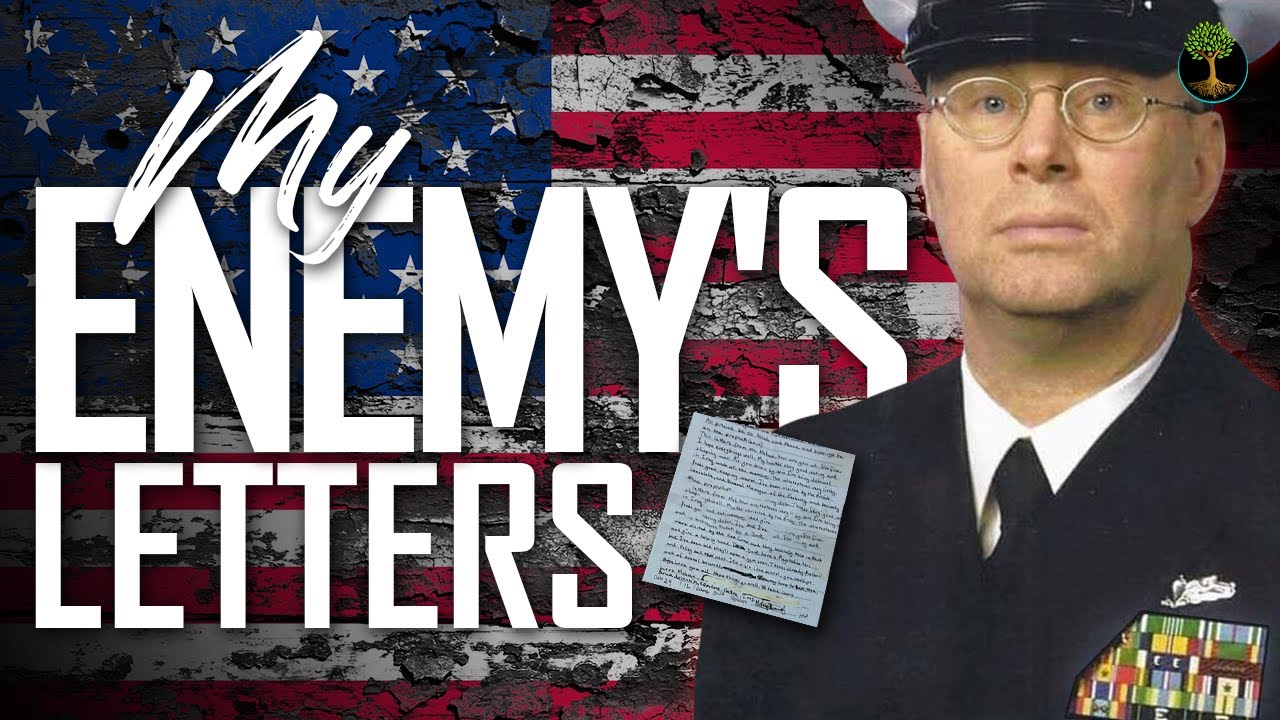

During his service in Iraq, Navy Corpsman Jim Enderle had an awakening experience that changed his life. The way he was taught to view the human beings he encountered with fear conflicted with his experiences that showed him a deeper humanity. In discovering it, he was able to heal himself from the post trauma of war. Jim Enderle uncovers what it means to be human and how it is only our perceptions that prevent us from truly achieving peace.

During my last military deployment, I had an awakening experience that changed my life. When our unit landed in Iraq, I thought “good” and “bad” were clearly defined. It wasn’t until I uncovered “My Enemies Letters” that I learned how wrong that perception was.

I served at a detention facility in Iraq as a Navy Hospital Corpsman. One positive tuberculosis case made us test the entire compound. And while doing so, I noticed one detainee looking at my name tag. Then he gleefully revealed something he had been holding – an envelope with my family’s name and address back in the United States. Terrified, I was certain he meant harm to my family.

A few weeks later, rockets and mortars struck the compound where this man was housed. I entered this blown apart compound to confront the man. Only I found him lying on the ground, badly wounded. Our eyes met, and time stood still, like we were the only two people on Earth. I had come to murder this adversary, but strangely, our expressions softened. He took a couple of uncomfortable breaths and extended his hand. I thought, “Is he asking for my help? For forgiveness?” As I stood frozen, he died right in front of me.

My senses soon returned, and I saw another man, maybe 30 feet away, struggling to help a badly wounded teenage boy. He shook him and seemed to say in Arabic, “Listen to me.. I am talking to you.” The father knelt with his back to me, caressing the boy’s face. As I came into his teenage son’s view, the boy’s eyes widened in abject terror upon seeing me, and then he died in his fathers arms.

Why would his teenage son be terrified of me, I wondered? I thought we were the “good guys”? After a moment of denial, the father let out an agonized, blood curdling cry that I hoped I would never hear again. I instinctively put my hand on his heaving shoulder, and, without knowing who was behind him beyond just a sympathetic figure, he put his hand over mine and squeezed. At that moment, we were just two fathers.

Curious about the humanity I saw in their eyes in their final moments, I asked my interpreter if I could learn more about the two men, and on my last day in Iraq, he gave me their translated personal letters. I didn’t know why I asked for them. I had promised myself that I wouldn’t bring the war home with me. Still, some cosmic reason told me to keep them.

I completed my deployment soon after and returned home. Unwilling to talk about the deployment, I substituted therapy with maladaptive behaviors. I wasn’t sleeping well, drank heavily, and abused prescription drugs. My marriage was shattered, reduced to a series of broken sentences. My paranoia made me booby trap my house for what I thought was an inevitable visit from militants seeking revenge. I contemplated suicide. –

Five years passed until I reluctantly read one of the letters that belonged to the deceased men. The men wrote about being internally displaced refugees that had seen all three innocent family members murdered in crossfire as Marines advanced in the al-Anbar Province.

The teenage boy, Abdul-Hayy, wrote Eye contact is essential for building trust in Arabic culture. The Americans have big sunglasses, like beetles, like robots. We look at strangers as guests in Iraq, as friends, and friends don’t bring guns to talk to their other friends. They don’t smile, and are really intimidating as they pass through. They don’t seem like rescuers at all.” He wrote, “America has satellites which can read my license plate, or tell which book I read as I sit on a park bench. They can buy the world three times over, and bomb the world to oblivion eight times, but there is no way to win our hearts and minds, but to drop from the ivory tower, look into our eyes, and shake our hands with respect and humanity.

The older man, Munawwar, the man who had my mother’s letters, lost his mother and sister in an explosion soon after becoming refugees. In his words, “Afterward, I felt as a mule which follows a path with no will of their own, looking downward, only seeing the path a few paces in front of them. That is their only challenge. The time it takes to cover that ground is all the time in the world.”

Two weeks later, his father was shot dead, caught in the middle of a firefight between American Marines and insurgents. Munawwar felt that true freedom was choosing to stay with his stricken father, even when the consequences were detention and the loss of his physical freedom. He felt that if you do right and suffer, you will have God’s approval. Still, Munawwar found a connection between grief and gratitude, writing, “When I lack, I look for what has endured, my memory of you. Father, you taught that I can be either a sword or a lens, through which others see and learn. Choose the sword, and negotiations end.”

When Munawwar showed me the envelope, that night he wanted me to know he was not “merely” Arabic, or “only” a refugee, or “just” a detainee, he was equally human. And he wondered “what would happen if a roomful of mothers, symphony composers, chefs, artists, and all those who create by taking distinct ingredients and blending them into a homogenous whole, would be the ones who could negotiate peace.” In his final entry, Munawwar shared that “I hoped to fill my life with curiosity and gratitude, before extending it outward, for two curious and grateful men find waging war against one another impossible.”

I was astounded by the beautiful sentiments in their letters that spoke of perseverance, gratitude, curiosity, and resilience. These letters were some of the most beautiful thoughts on life and love and the true cost of war that I had ever read and they came from people who we suspected to be “enemy combatants,” only it turns out they were never enemy combatants at all.

I began to heal and feel more alive as I learned about these honorable men. I wasn’t assigned an enemy, but a mentor. Through their stories and perspectives, I learned how to become human again. They were a healing elixir that helped me to heal and reunite with my family. I had to ask myself, “If there was one path to happiness, only one, and reuniting with my family hinged upon it, could I learn to forgive, respect, and even mourn the loss of my worst ‘enemy’?” In finding their humanity, I found my own.

I’ll never forget and I hope you won’t either, that…“Two men filled with curiosity and gratitude, find it impossible to wage war with one another.”

Jim Enderle is a native Chicagoan, retired Navy Chief Hospital Corpsman, and Iraq combat veteran. After his 2007 Iraq deployment, and finished his military career as the Chief of Submarine Base New London’s (CT) Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)/Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) outpatient clinic. He considers that time the most rewarding of his career.

Jim Enderle is a native Chicagoan, retired Navy Chief Hospital Corpsman, and Iraq combat veteran. After his 2007 Iraq deployment, and finished his military career as the Chief of Submarine Base New London’s (CT) Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)/Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) outpatient clinic. He considers that time the most rewarding of his career.

Jim has a Masters Degree in the Education of Exceptional Students and is a regularly scheduled speaker on veterans’ suicide and transition conversations. He’s done two TEDx Talks of lessons learned through stories told in the book. He hopes to apply for others.

Coming Soon.

For more info about Jim and his books, please visit his website.

During his service in Iraq, Navy Corpsman Jim Enderle had an awakening experience that changed his life. The way he was taught to view the human beings he encountered with fear conflicted with his experiences that showed him a deeper humanity. In discovering it, he was able to heal himself from the post trauma of war. Jim Enderle uncovers what it means to be human and how it is only our perceptions that prevent us from truly achieving peace.

During my last military deployment, I had an awakening experience that changed my life. When our unit landed in Iraq, I thought “good” and “bad” were clearly defined. It wasn’t until I uncovered “My Enemies Letters” that I learned how wrong that perception was.

I served at a detention facility in Iraq as a Navy Hospital Corpsman. One positive tuberculosis case made us test the entire compound. And while doing so, I noticed one detainee looking at my name tag. Then he gleefully revealed something he had been holding – an envelope with my family’s name and address back in the United States. Terrified, I was certain he meant harm to my family.

A few weeks later, rockets and mortars struck the compound where this man was housed. I entered this blown apart compound to confront the man. Only I found him lying on the ground, badly wounded. Our eyes met, and time stood still, like we were the only two people on Earth. I had come to murder this adversary, but strangely, our expressions softened. He took a couple of uncomfortable breaths and extended his hand. I thought, “Is he asking for my help? For forgiveness?” As I stood frozen, he died right in front of me.

My senses soon returned, and I saw another man, maybe 30 feet away, struggling to help a badly wounded teenage boy. He shook him and seemed to say in Arabic, “Listen to me.. I am talking to you.” The father knelt with his back to me, caressing the boy’s face. As I came into his teenage son’s view, the boy’s eyes widened in abject terror upon seeing me, and then he died in his fathers arms.

Why would his teenage son be terrified of me, I wondered? I thought we were the “good guys”? After a moment of denial, the father let out an agonized, blood curdling cry that I hoped I would never hear again. I instinctively put my hand on his heaving shoulder, and, without knowing who was behind him beyond just a sympathetic figure, he put his hand over mine and squeezed. At that moment, we were just two fathers.

Curious about the humanity I saw in their eyes in their final moments, I asked my interpreter if I could learn more about the two men, and on my last day in Iraq, he gave me their translated personal letters. I didn’t know why I asked for them. I had promised myself that I wouldn’t bring the war home with me. Still, some cosmic reason told me to keep them.

I completed my deployment soon after and returned home. Unwilling to talk about the deployment, I substituted therapy with maladaptive behaviors. I wasn’t sleeping well, drank heavily, and abused prescription drugs. My marriage was shattered, reduced to a series of broken sentences. My paranoia made me booby trap my house for what I thought was an inevitable visit from militants seeking revenge. I contemplated suicide. –

Five years passed until I reluctantly read one of the letters that belonged to the deceased men. The men wrote about being internally displaced refugees that had seen all three innocent family members murdered in crossfire as Marines advanced in the al-Anbar Province.

The teenage boy, Abdul-Hayy, wrote Eye contact is essential for building trust in Arabic culture. The Americans have big sunglasses, like beetles, like robots. We look at strangers as guests in Iraq, as friends, and friends don’t bring guns to talk to their other friends. They don’t smile, and are really intimidating as they pass through. They don’t seem like rescuers at all.” He wrote, “America has satellites which can read my license plate, or tell which book I read as I sit on a park bench. They can buy the world three times over, and bomb the world to oblivion eight times, but there is no way to win our hearts and minds, but to drop from the ivory tower, look into our eyes, and shake our hands with respect and humanity.

The older man, Munawwar, the man who had my mother’s letters, lost his mother and sister in an explosion soon after becoming refugees. In his words, “Afterward, I felt as a mule which follows a path with no will of their own, looking downward, only seeing the path a few paces in front of them. That is their only challenge. The time it takes to cover that ground is all the time in the world.”

Two weeks later, his father was shot dead, caught in the middle of a firefight between American Marines and insurgents. Munawwar felt that true freedom was choosing to stay with his stricken father, even when the consequences were detention and the loss of his physical freedom. He felt that if you do right and suffer, you will have God’s approval. Still, Munawwar found a connection between grief and gratitude, writing, “When I lack, I look for what has endured, my memory of you. Father, you taught that I can be either a sword or a lens, through which others see and learn. Choose the sword, and negotiations end.”

When Munawwar showed me the envelope, that night he wanted me to know he was not “merely” Arabic, or “only” a refugee, or “just” a detainee, he was equally human. And he wondered “what would happen if a roomful of mothers, symphony composers, chefs, artists, and all those who create by taking distinct ingredients and blending them into a homogenous whole, would be the ones who could negotiate peace.” In his final entry, Munawwar shared that “I hoped to fill my life with curiosity and gratitude, before extending it outward, for two curious and grateful men find waging war against one another impossible.”

I was astounded by the beautiful sentiments in their letters that spoke of perseverance, gratitude, curiosity, and resilience. These letters were some of the most beautiful thoughts on life and love and the true cost of war that I had ever read and they came from people who we suspected to be “enemy combatants,” only it turns out they were never enemy combatants at all.

I began to heal and feel more alive as I learned about these honorable men. I wasn’t assigned an enemy, but a mentor. Through their stories and perspectives, I learned how to become human again. They were a healing elixir that helped me to heal and reunite with my family. I had to ask myself, “If there was one path to happiness, only one, and reuniting with my family hinged upon it, could I learn to forgive, respect, and even mourn the loss of my worst ‘enemy’?” In finding their humanity, I found my own.

I’ll never forget and I hope you won’t either, that…“Two men filled with curiosity and gratitude, find it impossible to wage war with one another.”

Coming Soon.

For more info about Jim and his books, please visit his website.

Find out how video storytelling can help your audience resonate with your sustainable idea, research, campaign or product.

We never send solicitations or junk mail and we never give your address to anyone else.